I’m often amazed at how little time and thought some people put into career decisions. Considering how much of our waking hours we spend working and its potential impact on a lifetime of earnings you’d think we’d do our homework, seek technical guidance, and ask shailos before commiting to one field or another. But many don’t.

Narrowing the Field

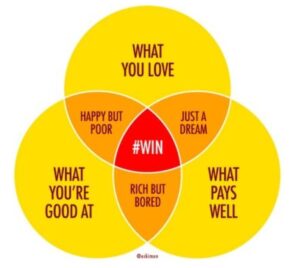

However one goes about it, deciding what to do for a living can be confusing. When people turn to me for career guidance, I usually don’t have much to tell them. One’s strengths, limitations, and preferences are difficult to quantify, so it’s challenging to narrow down the unlimited potential career paths out there, especially when starting with a blank slate. I was gratified, therefore, to find this insightful diagram. The infographic cleverly highlights key factors of a good career and helps put a logical framework on the journey to a job.

What Are You Good At?

It’s sensible to play to your strengths. Even someone who never got paid for their innate skills will likely know what they’re good at. A handy fellow may lean toward the trades, while someone numerically inclined will often go into fields stressing financial acumen. While any pursuit requires training and practice, having natural talent makes progress along that path easier. It’s also likely that when someone is good at something, they will get paid more for their excellence and enjoy their work more.

What Do You Love?

But just because someone is good at something doesn’t mean they’ll enjoy doing it day in, day out. I know of a lawyer, a dentist, and even rebbe’im who discovered after years of training and experience that they disliked their jobs. Ideally, we would work at something inherent to our nature. The Chovos Halevovos (Sha’ar Habitachon 3) says that one who has an inborn connection to a specific type of parnassah is clearly intended to pursue that hishtadlus, even if at times it doesn’t seem to be the most lucrative niche.

Work Is for Parnassah, Not Sipuk

This Chovos Halevovos is not as straightforward as some may assume, though. Rav Moshe Feinstein (Igros Moshe, Yoreh Dei’ah 4:35–36) was skeptical of those who said they were cut out only to be doctors or engineers, professions that would supposedly bring them “sipuk hanefesh.” He said that many people pursuing those tracks were seeking prestige, not their predestined professions. And he was puzzled by their equating careers with sipuk hanefesh, which only comes from ruchniyus endeavors, he writes. Clearly, there’s a difference between desiring a career for prestige or money, enjoying one’s work, and a deeper, spiritual satisfaction.

What Pays Well?

Even within the Chovos Halevavos’s guidelines, there still needs to be a hishtadlus angle to any parnassah. Talent and desire won’t help if they’re in a niche that no one pays for. It may seem silly, but there are gullible people being told to pursue solely what excites their passion—and those giving them this advice are often “self-help” promoters, colleges, or training programs that charge top dollar to teach about those “professions,” i.e., hobbies. A parnassah track must pay.

And it should preferably pay well. The Gemara in multiple places (eg. Pesachim 113A; Yevamos 63a) discusses industries that are especially lucrative, presumably encouraging people to consider pursuing them. We can theorize how these Gemaros fit with the Chovos Halevavos, which says one should not switch careers to pursue more money because it’s all bashert anyway, but clearly, money matters for hishtadlus.

Aiming for the Win

The diagram pithily lays out some scenarios (in orange) for those not fortunate enough to hit the winning spot. Ideally, a career will intersect all three segments, being something the person is good at, enjoys doing, and pays well. In reality, though, the need to pursue parnassah is a klallah, and jobs often don’t work out that neatly. It’s wise to try and minimize that curse, but, especially at the outset, many sweat quite a bit to bring home their bread. Still, by keeping the three-question framework in mind, you can hopefully navigate in the right direction.

The Crucial Fourth Dimension

The three-question framework described above is clever but leaves out the crucial fourth dimension: what Hashem wants. The Mishnah (Kiddushin 4:13–14) is very explicit that people should avoid parnassah paths that, even if not forbidden, may lead them in the wrong direction. Whether this includes potential breaches of tznius or consistent temptations to steal and cheat, a frum person should seriously consider what lies in store. “Eizehu chacham haro’eh es hanolad (Tamid 32a).” A career path that offers material wealth and comfort at the expense of adherence to Yiddishkeit is a trap, not an opportunity.

Similarly, the Mishnah recommends careers that enhance ruchniyus by leaving time and focus for Torah. Obviously, klei kodesh, whether directly on the front lines or in the background, is an excellent choice for a frum Jew, if possible. Pursuing that path will surely maximize the sipuk hanefesh R’ Moshe refers to.

Try Your Best

I hope you found this perspective illuminating. It’s worthwhile to note that these kinds of questions may arise at multiple junctures in one’s life. The initial decisions one makes before choosing their first job may become moot as life evolves, industries shift, and we learn more about what we’re good at and enjoy. By approaching our parnassah paths with bitachon and measured intelligence, BH everyone will find their umnus kallah unekiah.

Want to dig deeper?

Try these related articles

Expanding Parnassah Options

Helping your Child Land their First Job

Sell What You Know