Duvie Katz wasn’t a mathematician, but even he realized that four daughters x weddings + support = much more money than he had saved. A fellow in his shul was encouraging him to buy a $250,000 “chasunah policy” by investing $4,000 a year for 20 years into a whole life insurance (WLI) policy. This investment would supposedly grow into a cash-value pot of $250,000 or more, available for chasunah expenses.

If chas v’shalom he would die at any time during the 20 years, the $250,000 was immediately guaranteed as a death benefit. Duvie did not need any more life insurance—he had a significant term policy from work—but this plan was supposedly a safe way to grow his savings; the extra coverage was just icing on the cake. While locking up $4,000 a year was very difficult for the Katz family, if doing so would cover their wedding expenses, Duvie was ready to push himself.

Should Duvie buy life insurance coverage he doesn’t need just for investment purposes? What kind of investment growth should he expect from WLI?

A Niche Tool

WLI, a complex product which mixes life insurance and investing, is a spork among financial utensils. A spork, a combination of a spoon and a fork, is useful to those who are tight on space, such as hikers and travelers. But if Mrs. Katz needs a new set of spoons and Duvie brings home sporks instead, she will not be pleased. Even the best spork is neither a very good fork nor an excellent spoon; it’s a niche product that sacrifices some of the ability of each function in order to save space.

So too, while some people (mainly the very wealthy) can benefit from combining their investing and life insurance into one package, neither the investing nor the insurance part of WLI works as well as the stand-alone products do individually. Since Duvie doesn’t need the insurance part of the tool, a WLI “spork” is not the best way for him to invest.

Significant Risk and Low Returns

If Duvie digs into the details of the suggested policy, he’ll discover that the investment returns of the recommended WLI policy over 20 years are meager. The policy has negative returns for 10 years—if he cashes out during that time, up to 80% of his investment will be lost (due to fees and commissions)! If Duvie does stick it out for 20 years (investing $4,000 x 20 years = $80,000), the annual returns will be between 1.7% and 3.2%, with the cash-value pot growing to just $94,338–$110,00 pretax.

Unless someone locks into a WLI policy for many decades, they can make more from CDs and bonds with much less risk (the substantial penalties if they can’t make their annual payment at some point). More importantly, this investment will leave Duvie well short of the $250,000 required for his weddings. That number, mentioned by the broker, is guaranteed only on the insurance side if he dies.

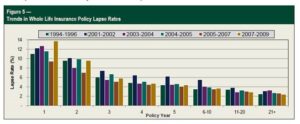

From an insurance perspective, WLI is an inferior option to a term policy in one important way: to enable the investment cash value to grow, a combination insurance-investment policy costs about 10 times more than plain life insurance. Therefore, many families who use WLI can only afford policies with small death benefits, leaving them underinsured. If they can’t meet the hefty annual payments within the first few years, the plan gets canceled, and they forfeit most of the money they’d put into it.

This lapsing of WLI is not an unusual occurrence. Furthermore, once burned by the industry, these families may remain entirely unprotected. In Duvie’s case, the insurance part of WLI isn’t an issue since he doesn’t even need it. But need it or not, he is still paying for the cost of insurance (the guaranteed $250,000 paid if he dies), which limits his investment growth.

But a Possible Remedy for Overspenders

Although WLI doesn’t grow very much and the Katzes can get significantly higher returns with a balanced mutual fund portfolio, WLI can still work for them. In fact, WLI’s heavy-handedness, which penalizes policyholders for not continually making their payments, is in one way a major advantage over other investment strategies. Many people have no savings discipline, and WLI’s restrictive structure may remedy that since facing losses if they stop putting money into a policy forces them to keep on saving. If this describes Duvie, he should take his WLI “medicine.”

Whatever investment path they choose, to build a $250,000 portfolio in 20 years the Katz family will have to save a lot more than $4,000 a year. The most critical ingredient of financial success is accumulating savings, not squeezing every possible percent of growth out of them.

Just by the Way: A Warning from the Wastebasket

Imagine noticing, near the exit of a bakery, a wastebasket full of cookies with only one bite missing from each. Wouldn’t you think long and hard before buying one of that type of cookie? As its name implies, WLI is designed to be a very long-term product, yet very few keep it long enough to reap its full benefits. Since many WLI policy customers regret buying it, people should research and think carefully before agreeing to this expensive commitment. Do you understand all the terms? Can you afford to hold the policy for a very long time? If not, then don’t start one. But once you’re invested into a WLI policy, don’t just drop it in the wastebasket. WLI can perform reasonably well—but only when used as intended.

Want to dig deeper?

Try these related articles

Whole Life Insurance: Follow The Facts, Not Stories